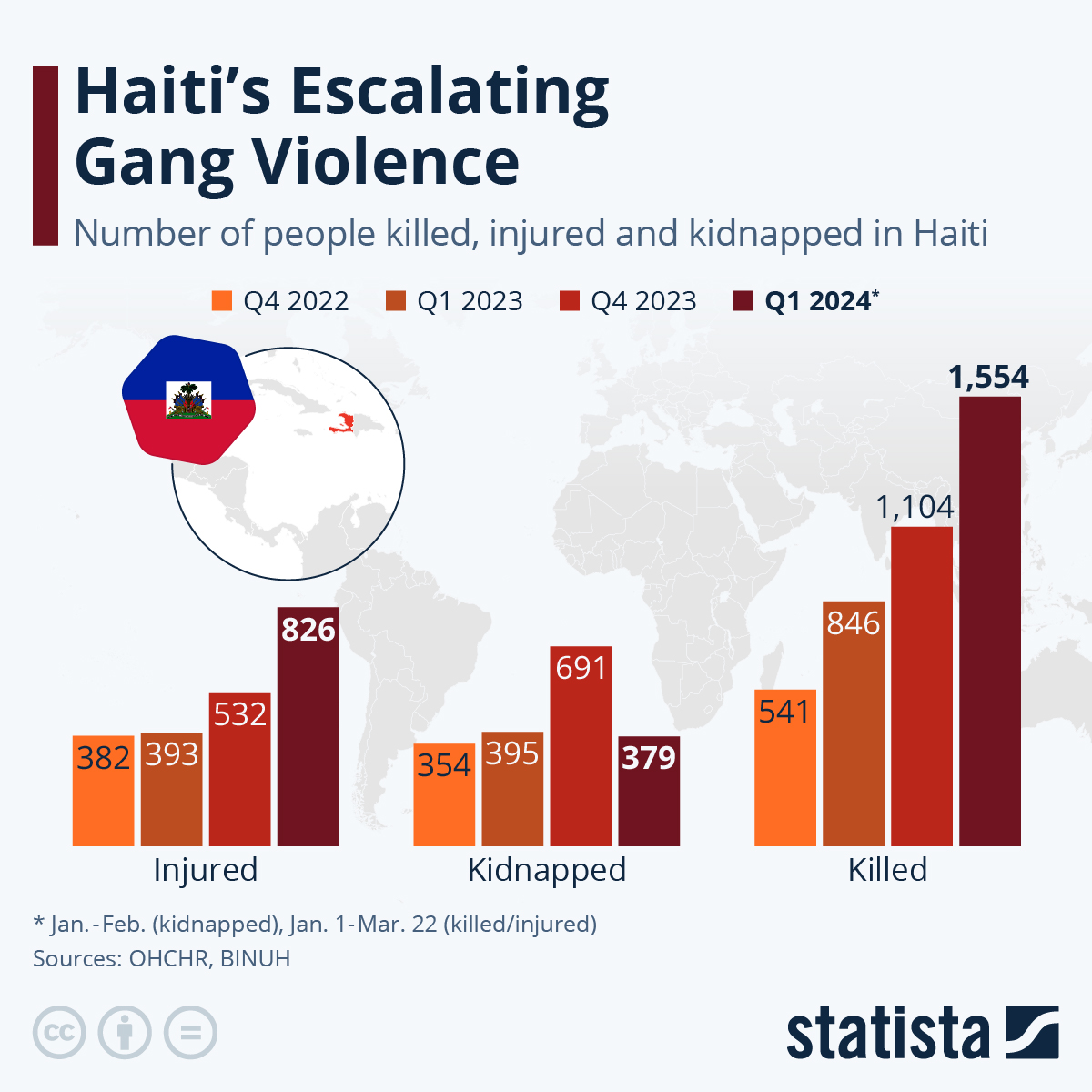

Violence in Haiti claimed the lives of at least 1,554 people in the first three months of 2024, according to a report released by the UN Human Rights Office last week. The report called for "immediate and bold action to tackle the 'cataclysmic' situation" in the country and said that "corruption, impunity and poor governance, compounded by increasing levels of gang violence" were to blame for state institutions having been brought close to collapse. Compared to the previous quarter as well as Q4 of 2022 and Q1 of 2023, the number of killed and injured Haitians has increased significantly.

An estimated 53,000 people are believed to have fled the capital Port-au-Prince between early March and early April alone due to the desolate situation. Many are joining 116,000 previously displaced persons in the rural South of the country, stretching resources thin there.

The country has been facing a particularly intensive period of political and social crisis since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021. Following his death, the ensuing power vacuum has been filled by rival gangs, while Moïse’s successor, Prime Minister Ariel Henry, has faced challenges over his legitimacy within the country and finally resigned in mid-March.

Tom Phillips of The Guardian draws attention to the complexity of the situation, highlighting how the country’s overlapping crises are rooted also in a history of international interventions, including the U.S. occupation from 1915-1934, as well as the impacts of “reparations” to France, and the devastating earthquake of 2010 that killed up to 300,000 people.

Both Prime Minister Henry and the UN High Commissioner Volker Türk have called on the international community to deploy a time-bound “specialized support force” to assist the country's authorities. However, some Haitians reject the proposal of international intervention based on past experiences of foreign forces in the country.