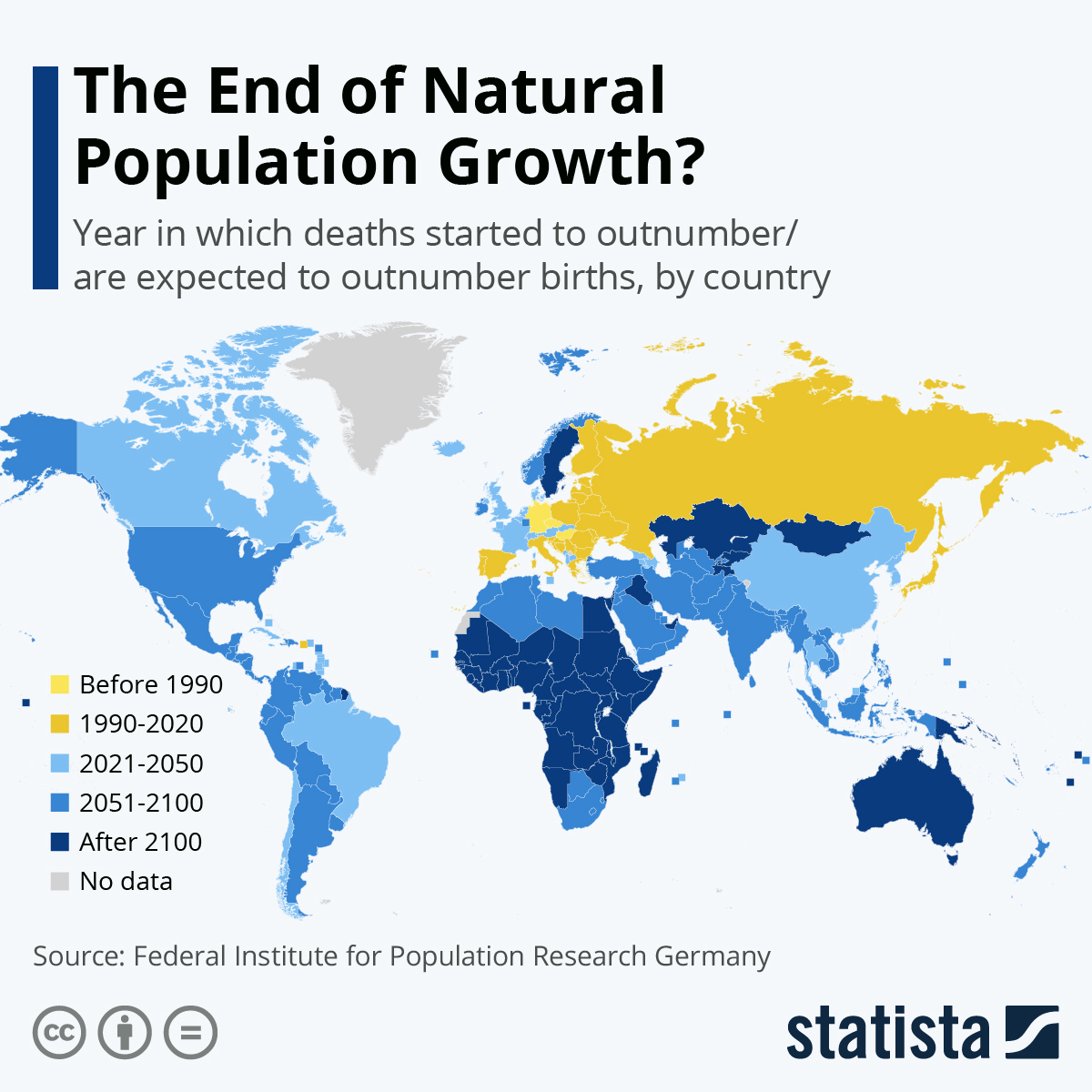

The number of countries experiencing more deaths than births in a given year is steadily increasing. An analysis of U.N. data by the Federal Institute for Population Research out of Germany shows that the "natural balance" of births and deaths is declining worldwide, causing aging and even decreasing populations.

Germany was the first country in the world to experience a surplus of deaths. Every year since 1972, fewer people were born there than died. Before 1990, this also started happening in Hungary (1982) and the Czech Republic (1986). By the middle of the current century, however, all countries in Europe, with the exception of Norway and Sweden, are expected to see natural natural population growth turn negative. Populous countries such as Brazil and China are also projected to experience this change before 2050.

Past 2100, most naturally growing countries will be found in Africa, with some also persisting on the Arabian Peninsula, in Oceania and in Central Asia. Sweden is the only European country expected to keep up natural population growth past that date.

But a surplus of deaths does not automatically mean that a population is shrinking. Migration also plays a major role in the equation and can prop up population growth if a country is able to attract (and willing to admit) enough migrants. Germany, despite its long history of net negative births, benefits from an immigration surplus, meaning that more people immigrate to the country than emigrate in most years, with the effect that its population continues to grow slightly. Other European countries – mainly in the Eastern part of the continent – have been less successful in fostering immigration, which caused their overall population growth to turn negative.

Japan is another example of a developed country that until recently was not partial to immigration, also placing it on the list of shrinking countries due to its death surplus. The same fate is expected for South Korea and China, two more Asian countries with declining births that haven’t positioned themselves as migration recipients.