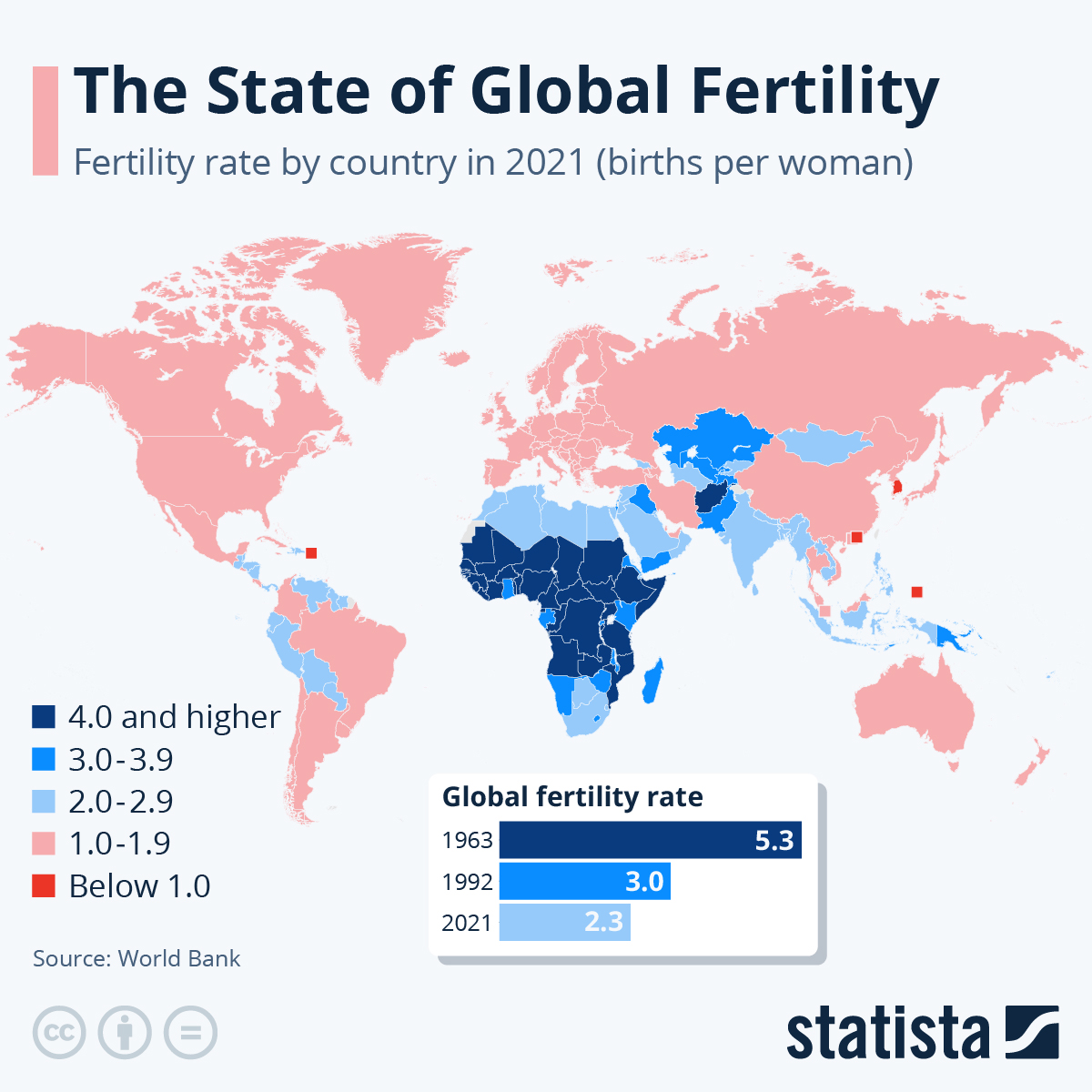

South Korea broke its own record when it announced today that as of 2023, its fertility rate had fallen to just 0.72 births per woman. The rate at which a population replaces itself between generations without migration stands at around 2.1. A map with comparable data between countries from 2021 shows that even then South Korea was one of only a few places in the world with a fertility rate below 1.

In Japan, which on Tuesday announced a 5 percent decline in births to a record low of 758,631, the birth rate remained at 1.26. This places the country among the approximately 90 in the world where populations are not growing independent of immigration. Also in this group are many nations from Europe, the Americas and Southeast Asia. Most of the countries losing fertility are better developed and reasons for the trend include greater access to contraception and more women being educated and heading to work.

The story is different in the developing world where higher rates of fertility are fueling continued global population growth. The West African country of Niger had a fertility rate of 6.8 in 2021, the highest in the world listed by the World Bank, followed by Somalia, Chad and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Out of the 33 countries in the world where women had 4 or more children on average, 31 were in Africa that year.

On average, women in 1963 were having 5.3 children in their lifetime and by 2021, that had more than halved to 2.3. During the same period, the global population rose by around 150 percent from 3.2 billion to 7.9 billion. The fact that populations kept (and keep) growing despite falling global fertility is tied to longer life expectancy and lower childhood mortality. The UN expects global fertility to reach the minumum replacement level of 2.1 by the middle of the century while global population is expected to start falling towards the end of it.